Vintage watches and ‘patina’

The man who said no to a Rolex Red Submariner

6 May 2019

A great Strap for Vintage Watches: The Geckota Radstock Leather Strap

28 September 2020We leave you a new installment of Erik Van Woerkens for our Blog. After illustrating us, in his previous articles The case size of a wristwatch and others decisive factors that itfluence its comfort on the wrist and In-house versus third-party mechanical watch movements, Erik reflects on this occasion on the patina in watches and the difference between beauty and deterioration. This article, in my opinion, is one of the most accurate I have ever read on this topic. Thanks Erik. You have scored a “Maradonian goal” again 😉

WRITTEN BY

ERIK VAN WOERKENS

If you are familiar with Watches83.com you are well aware that vintage watches are becoming more and more popular with collectors worldwide. In earlier days of our hobby vintage watches had to be restored and polished to look “like new”. But nowadays we see more aged timepieces on offer that are well-worn and show dings, fading and scratching. It is for sure a sign that the majority of collectors have started prizing originality over restoration.

Originality

Often when you see vintage watches advertised for sale, you often see the words patina and tropical announced. What does that mean? What is patina? When is it seen as patina, and when should it be regarded as ‘just plain damage’?

Originality of a vintage timepiece is crucial and often that is extremely difficult to find nowadays. In earlier decades popular brands like Rolex and Omega serviced their popular Submariner and Speedmaster models back to an ‘as new’ standard they often used new original parts which were from other references. Faded bezels were replaced with brand new ones and so on.

Looking new was more important than being original and selecting the exact parts. This has changed completely: originality is key.

What is watch patina?

Watch patina refers to a natural process of aging of timepieces, it describes the visual state of hour markers, hands and/or dial that has altered with age. An original vintage watch clearly shows sign of the time: hour markers or numerals on the dial often have turned into a lovely yellowish, creamy, amber or a brownish color. Sometimes it would get a somewhat green color. And so have the hour and the minute hands.

The dial and bezel may have another color compared to when they left the factory. White dials may have gotten a creamy color. Black dials may have turned greyish or brownish. The latter is very much sought after, and is called tropical. A black bezel may have turned light grey.

The patina is unique on each watch, there is no one like it with exactly the same patina.

History of a watch

We collectors look at patina as extra character of the watch. Every scratch and faded numeral represents a story of the watch’s past. Honest patina is showing after a long life of being worn and loved by the owner and can have unique effects. I personally like to wonder about the rich history of an old watch: who may have worn this timepiece back in the fifties or sixties? Which places has this watch been to?

What is patina?

Watches with the right patina are more popular and more expensive. So, I was interested in learning more about what patina really is, how that process of discoloration takes place.

There are many factors that cause patina in watches; they change in time, and also differ from watch to watch. The aging of your watch is mainly affected by light, moisture and humidity, usage and materials.

The contents of your watch play an important role in making the patina look: what material was used for the hands, what paint was applied to the dial, which type of luminescence was used.

My personal experience is that I noticed a serious difference of patina on the same models of watches: Omega 145.012 is prone to get a chocolate dial, Omega Seamaster 30 is likely to be turned into a suntanned creamy dial instead of the original white one. Clearly some paints were changed over the years by Omega.

My personal patina Omega Seamaster 30 and Omega 105.012-65 Speedmaster

MOISTURE AND HUMIDITY

We don’t want water to penetrate into the case. It is a disaster for the movement obviously because rust will build on the gear, screws, escapement, balance wheel and main spring.

But also the dial side of the watch will be affected by humidity. Circles of dried up humidity, uneven stains and spots on the dial etc. There is a very fine line between esthetically pleasing patina and ‘just plain damage’.

Through the years I ‘ve noticed a connection between lume discoloration and moisture: the better (the more waterproof) the case, the less a watch is likely to get moisture inside the watch, and the more pleasing the lume will become for the eye.

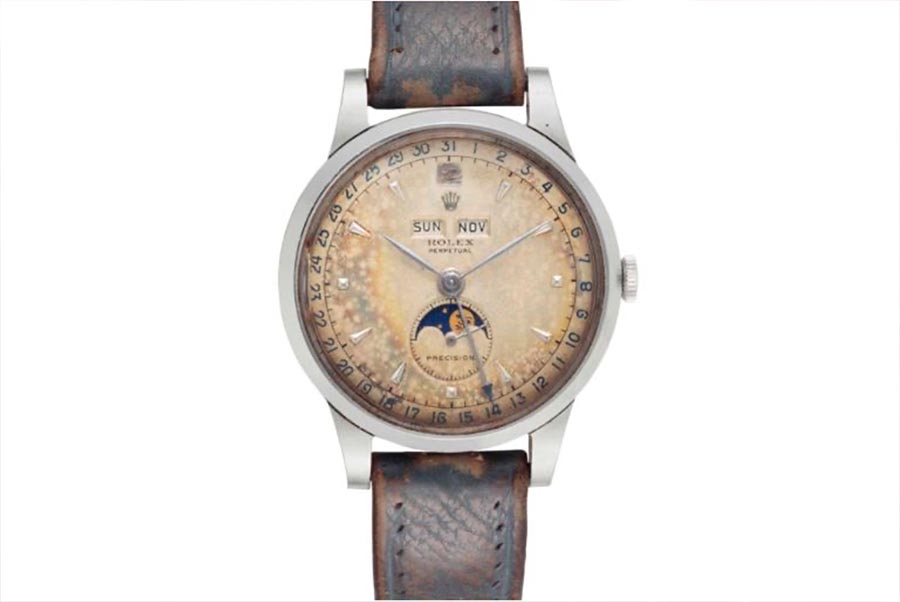

Rolex with heavily stained dial at Christies that sold for 70.000£

Environmental influence

Temperature as well as exposure to sunlight and UV will dissolve the lacquer after a long while. Painted dials can start to peel off, or cracks appear.

Some examples from the shop Watches83.com: Rolex Tudor and Anonimous

Dials

Dials of really-old watches were all metal. In the nineteenth century, the process of making white, cream or sometimes black, rings with enamel, a glass coating on a copper plate, was developed.

The word ‘enamel’ originally simply meant ‘a coating’. Enamel dials usually have a glassy reflective surface and they are resistant to patina (although they can crack quite easily).

Enamel items were expensive to make, so in the twentieth century, cheaper materials were used, usually by painting or printing on a metal base. Those are prone to discoloring, cracking, fading and spotting. The paint used will determine how well or bad it will sustain time and sunlight.

By exception a black dial will discolor into a warm chocolate brown color, this is called a tropical dial. Tropical dials are very much sought after and expensive.

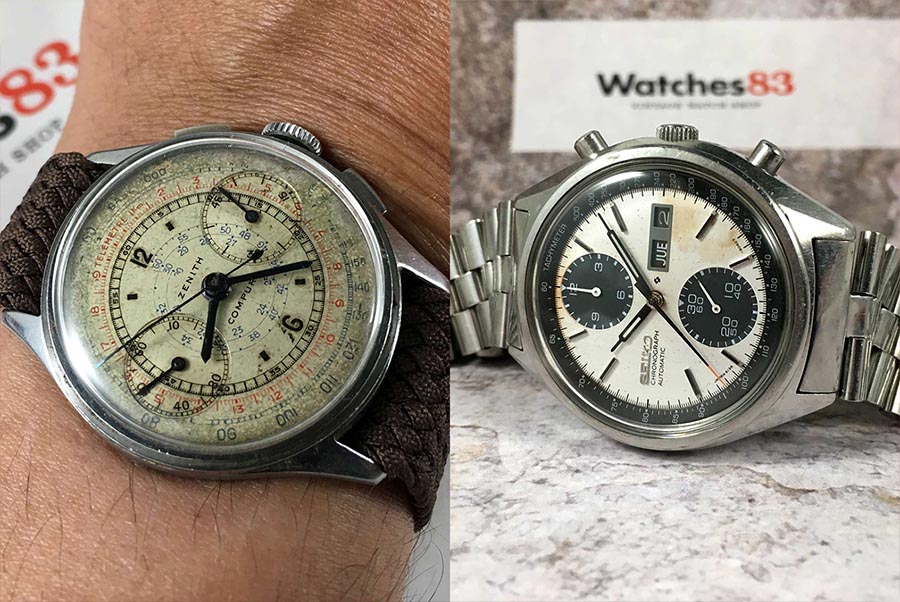

Dials that turned brown are highly wanted (Examples: Zenith Compur, Seiko Panda Chronograph, Universal Geneve Polerouter)

Materials used for luminous accents

Talking lume, most people are aware that the watch industry has gone through an evolution. The reason being serious health issues when older radio-active paints were used. The industry saw an evolution from using radium to tritium and eventually superluminova.

Faded and disappeared Tritium (Examples: Neptune and Sandoz)

A bit of history about lume

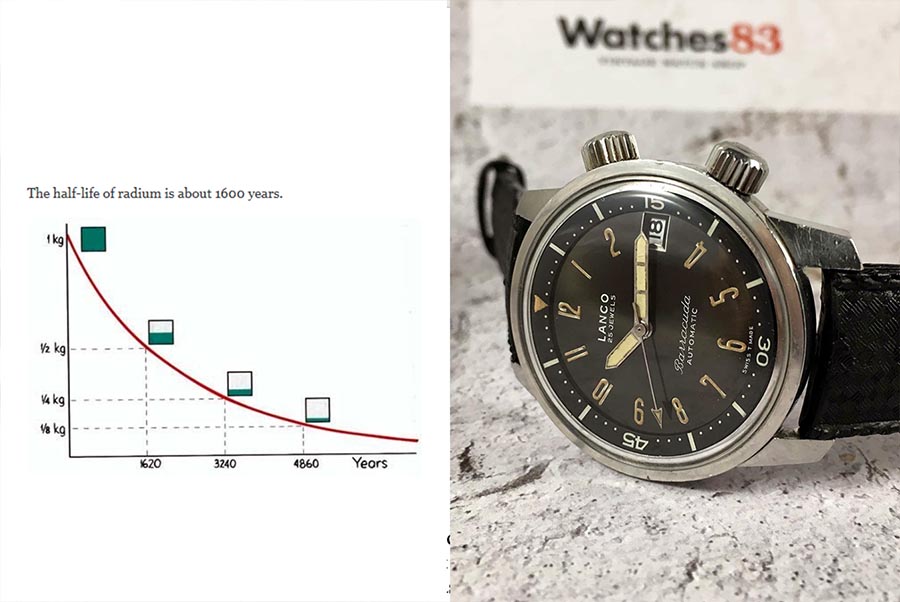

Military use was again the driver for changing direction in watches: the first application of luminous paint (lume) can be found on military pocket watches from the early 1900s. Initially, luminescence was achieved by using a radioactive material that is called radium, which was discovered by Marie Curie and her husband, Pierre Curie in 1898. Radium was eventually combined with zinc sulfite, allowing a brighter shine than just pure radium. Even after it was proven that radium exposure was harmful at the end of the 1920s, it was still used sparingly until the early 1960s. Because of the hazards, watch factories implemented safety protocols, but radium continued to be used on dials. Because radium was unsafe, tritium became the newly used luminous material in the early sixties. Just like radium, tritium was also radioactive; however, it came with a much lower level of radiation and a much shorter half-life.

Source: wikipedia A Lanco with plenty of aged Tritium

While tritium was far more safe than radium, it also had a half-life of only twelve point three years (radiums’ half-life is 1620 years!). This meant that after some 50 years, only a tiny fraction of the initial luminescence would remain. Additionally, as tritium ages, not only the color changes (which creates interesting patinas on the luminous markers of older watches) but also the luminous properties disappear (this was the reason for Rolex and Omega to replace older hands and dials during a service. All had to look like new again…). Despite being substantially safer than radium, tritium was still radioactive, and as a result, many watchmakers of the time marked the dials with an indication of the level of radioactivity of the watch dial, such as “T Swiss T”, or “Swiss T<25”. Tritium was far from perfect, which lead to watch companies search for a better alternative.

All radium on dials will have built a dark orange-brown shade by now. Radiation of radium is not dangerous as long as the crystal still sits on the watch.

Tritium Lume will never discolor in the same way however. Most people experience “a nice patina” as when tritium lume has evolved to ‘a nice cream, yellow or darker’shade. Conditions with no moisture as essential for tritium to build this beloved shade. However when moisture was present is the watch, most tritium will have disappeared and only the (greenish) paint that sits below the tritium, will remain. This is the case with a great lot of vintage watches with tritium that have turned rather green in color. In fact this can be considered as being damage due to moisture ingress.

A solution was found during the 1990’s, by a Japanese company called Nemoto and Co., which specialized in producing luminous paint. Their new compound, called Luminova, was photoluminescent rather than radioactive, making it entirely harmless. Additionally, it was not prone to fading or discoloration like its predecessors, radium and tritium.

Why is it that some tritium has remained white while it turned cream/yellow or brown on others? Lume patina is directly related to the amount of NATURAL light the dial is exposed to. More frequent light (read: daily wear) will keep the lume almost white. Watches that were “locked up”; in a dark place will have a lot of patina. So called ‘safe queens’ will not only have nicer patina but also a less banged-up watch case.

Tritium on hour and minute hands tends to age slightly less than the tritium on numerals or hour markers. The reason for this is that discoloration will be more visible on surfaces where the luminous paint was applied thicker.

Patina or wear?

When talking patina, we are talking the dial, the bezel, the hands, and the hour markers. There might be signs of oxidation on the movement, but that typically is a bad sign. A sign of water that got into the case.

Worth more?

There is no denying that patina timepieces are trendy. Auction houses like Phillips and Christie’s have seen much higher closing prices for vintage watches with nice patina in the past 5 years. The growing interest is obvious since vintage watch collectors are more numerous now than just 5 or 10 years ago, and patina watches few are unique. This has led to faking patina on vintage watches in recent years, again your research is requested before buying that one cool vintage patina watch.