In-house versus third-party mechanical watch movements (Part 1/2)

Homage watch series: Eterna-Matic Kontiki

11 October 2018

In-house versus third-party mechanical watch movements (Part 2/2)

29 November 2018“In Watches83 we have considered this article by our friend Erik so accurate, complex and brilliant, that we have decided to divide it into two parts. Today we publish the first part. Thanks Erik for giving us this jewel ;-)”

WRITTEN BY

ERIK VAN WOERKENS

Today I am going to speak for the readers of the BLOG of Watches83 about the heart of the watch. The topic of what’s inside your watch, has been playing a role for plus 100 years already, and it has become even more important. Marketing an in-house movement has become THE way for watch brands to diversify themselves from competitors in recent years; THE way get up on the ladder of prestige in the horology world. Don’t take this blog too serious though, don’t blame me for my viewpoints, but rather make up your own conclusion, based on some thoughts mentioned below. Here we go.

There is a feeling of pre-eminence with owners of a watch with an in-house movement. They will use several reasons why in-house movements are better: exclusivity, the level of manual finish, the pristine polished plates and manual bevels on hundreds of miniscule parts, and last but not least: its high price. Exclusivity and manual craftsmanship can be a reason for some to want such a unique movement, but is it the better choice?

To begin with the past, let’s just admit that not all luxury brands with lots of history have always used their own in-house movements in the past. Some did it because of economics, short leadtimes for launching a new model, or just because of the lack of a fitting own movement.

- It might surprise you, but Rolex has sourced third-party movements from the Aegler between 1905 and 2004. For hundred years! Rolex?! Yes indeed. For some time this cooperation became so tight that Aegler was bound to produce movements exclusively for Rolex. Aegler was even forced to put the name ROLEX on the movement, pretending Rolex made the movement themselves. Aegler was not allowed to produce for other watch brands, and even up to the point that both company owners also owned a part of the other company (Rolex owners owned a part of Aegler, and vice versa). For years there has even been a Rolex sign on the front of the Aegler building. But Aegler stayed independent until Rolex bought it in 2004. (Source Watchfinder UK).

- Rolex used the Valjoux-72 movement (Valjoux is now owned by ETA) in the Cosmograph lines of chronographs, later on renamed to Daytona for marketing reasons. Rolex used a heavily modified Zenith El Primero in their Daytona chronographs.

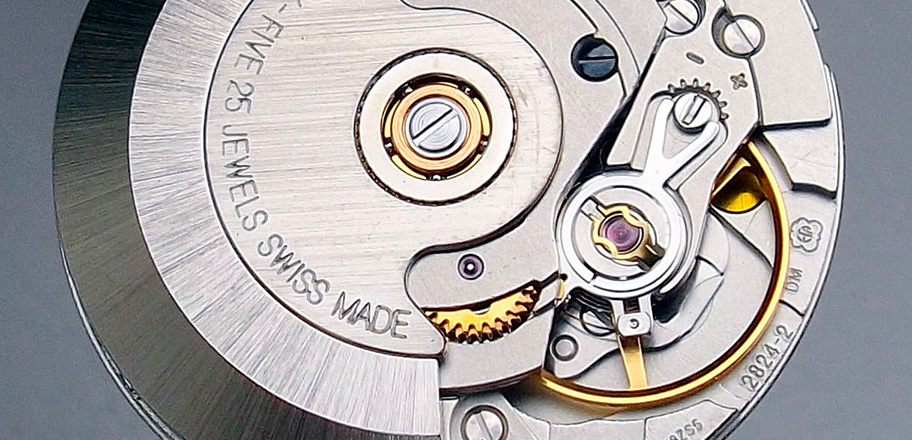

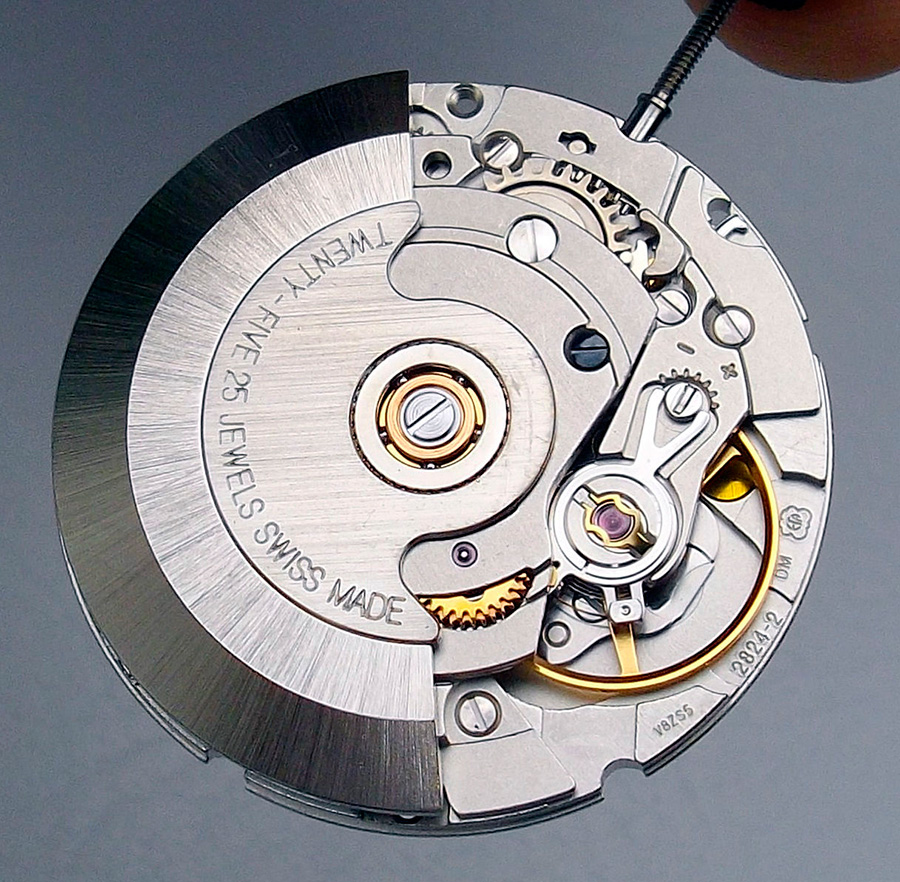

- Tudor, also owned by Rolex, has exclusively used ETA movements until recently (2015) when they decided to start building an in-house movement to be used in some models (not all Tudor watches are equipped with in-house movements yet, think of the Black Bay 36). Even the highly appreciated Tudor Pelagos and Tudor Black Bay diver watches were using an ETA 2824-2 movement until 2015 (ETA-2824 no-date for the Black Bay, ETA-2824 with date for the Pelagos) or ETA-2892 with Dubois-Depraz module for the Heritage chronograph. And now all of a sudden, ETA is considered less in regard since Tudor has started with in-house movements. Try to get this change of appreciation if you can.

Eta 2824-2 (Source: Ebay)

- In the past, even the most highly rated luxury watch brands that form the ‘holy trinity’ in the watch world (Patek Philippe, Vachéron Constantin and Audemars Piguet) have used movements that were supplied by Jaeger LeCoultre for a very long time. JLC still has a very heavy research & development department for movements, used as a starting point for PP, AP and VC.

- Another example is that of Omega that has used modified ETA movements exclusively in all of the automatic Speedmasters until 1999 when Omega launched their first caliber 2500 with a co-axial escapement.

Omega 2500 with Co-Axial-escapement (Source: Monochrome-watches.com)

The first summary is that even the highest level of watch brands have sourced movements from other manufacturers for many years.

Then there is the thing of brands that are pretending they are using their own caliber but in fact they are just renaming an existing ETA-movement like Longines has done in the past 40 years with the majority of their models. Or the recent cooperation between Tudor and Breitling where both pretend to use their own caliber but in fact they are using each others’ movements with some minor changes (machined surface finishing and the naming). The thing is that “in-house” has become a marketing trick anno 2018, no matter the truth behind it.

Second summary is that watch brands that are still using insourced movements nowadays, are often hiding that fact by giving the movement an in-house name, a “caliber”.

Up till today, some brands keep on maximizing their profit by modifying an ETA movements for the entry level of their collection (and rebrand it like it is an in-house movement), and use real in-house movements for the higher end models. Think of IWC, Panerai.

Third summary is: do your homework before you buy, don’t expect to hear the truth for the reseller. Not all name-branded calibers are in-house movements.

In-house or generic watch movements (ETA and the like)? Both types of movement serve specific purposes and one is not necessarily better than the other.

- Quite a lot of in-house movements have been based on ETA or Valjoux ébauches (the basic movement) and then luxury brands add modules to create a house movement that serves specific complications. Examples: The majority of movements in vintage Omegas. All of the current in-house movements in Habring2

- Another thing that happens a lot is that watch brands start to enhance ETA-movements: they take the purchased off-the-shelf movement apart again and add decoration to the different minuscule components, or they enhance the accuracy by reducing tolerances and deviations of the off-the-shelf movements. Both activities require manual craftsmanschip, and is labour/cost intensive.